Decay¶

| Author: | Anthony Scopatz |

|---|

The Bateman equations governing radioactive decay are an important subexpression of generalized transmutation equations. In many cases, it is desirable to compute decay on its own, outside of the presence of an neutron or photon field. In this case radioactive decay is a function solely on intrinsic physical parameters, namely half-lives. This document recasts the Bateman equations into a form that is better suited for computation than the traditional expression.

Canonical Bateman Equations for Decay¶

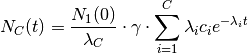

The canonical expression of the Bateman equations for a decay chain

proceeding from a nuclide  to a nuclide

to a nuclide  at time

at time

following a specific path is as follows [1]:

following a specific path is as follows [1]:

The symbols in this expression have the following meaning:

| symbol | meaning |

|---|---|

|

length of the decay chain |

|

index for ith species, on range [1, C] |

|

index for jth species, on range [1, C] |

|

time [seconds] |

|

number density of the ith species at time t |

|

half-life of the ith species |

|

decay constant of ith species,  |

|

The total branch ratio for this chain |

Additionally,  is defined as:

is defined as:

Furthermore, the total chain branch ratio is defined as the product of the branch ratio between any two species [2]:

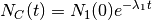

Minor modifications are needed for terminal species: the first nuclide of a

decay chain and the ending stable species. By setting  , the Bateman

equations can be reduced to simply:

, the Bateman

equations can be reduced to simply:

For stable species, the appropriate equation is derived by taking the limit

of when the decay constant of the stable nuclide ( ) goes to

zero. Also notice that every

) goes to

zero. Also notice that every  contains exactly one

contains exactly one  in the numerator which cancels with the

in the numerator which cancels with the  in the denominator

in front of the summation:

in the denominator

in front of the summation:

![\lim_{\lambda_C \to 0} N_C(t) = N_1(0) \gamma \left[e^{-0t} + \sum_{i=1}^{C-1} \lambda_i \left(\frac{1}{0 - \lambda_i} \prod_{j=1,i\ne j}^{C-1} \frac{\lambda_j}{\lambda_j - \lambda_i} \right) e^{-\lambda_i t} \right]

N_C(t) = N_1(0) \gamma \left[1.0 - \sum_{i=1}^{C-1} \left(\prod_{j=1,i\ne j}^{C-1} \frac{\lambda_j}{\lambda_j - \lambda_i} \right) e^{-\lambda_i t} \right]](../_images/math/e89d8b67cc10603ec59c692d2387d039ca552b20.png)

Binary Reformulation of Bateman Equations¶

There are two main strategies can be used to construct a version of these equations that is better suited to computation, if not clarity.

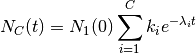

First, lets aim for minimizing the number of operations that must be performed to achieve the same result. This can be done by grouping constants together and pre-calculating them. This saves the computer from having to perform the same operations at run time. It is possible to express the Bateman equations as a simple sum of exponentials

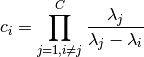

where the coefficients  are defined as:

are defined as:

If  are computed at run time then the this expression results in much more

computational effort that than the original Bateman equations since

are computed at run time then the this expression results in much more

computational effort that than the original Bateman equations since  are brought into the summation. However, when

are brought into the summation. However, when  are pre-caluclated,

many floating point operations are saved by avoiding explicitly computing

are pre-caluclated,

many floating point operations are saved by avoiding explicitly computing  .

.

The second strategy is to note that computers are much better at dealing with powers of

2 then then any other base, even  . Thus the

. Thus the exp2(x) function, or  ,

is faster than the natural exponential function

,

is faster than the natural exponential function exp(x),  . As proof of this

the following are some simple timing results:

. As proof of this

the following are some simple timing results:

In [1]: import numpy as np

In [2]: r = np.random.random(1000) / np.random.random(1000)

In [3]: %timeit np.exp(r)

10000 loops, best of 3: 26.6 µs per loop

In [4]: %timeit np.exp2(r)

10000 loops, best of 3: 20.1 µs per loop

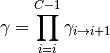

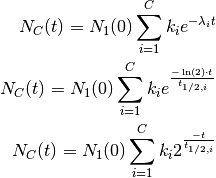

This is a savings of about 25%. Since the core of the Bateman equations are exponentials, it is worthwhile to squeeze this algorithm as much as possible. Luckily, the decay constant provides an intrinsic mechanism to convert to base-2:

This expression can be further collapsed by defining  to be the precomputed

exponent values:

to be the precomputed

exponent values:

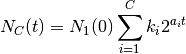

Thus, the final form of the binary representation of the Bateman equations are as follows:

General Formulation:

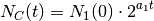

First Nuclide in Chain:

Stable Nuclide:

![N_C(t) = N_1(0) \left[1.0 + \sum_{i=1}^{C-1} \lim_{\lambda_C\to 0}(k_{i}) \cdot 2^{a_i t} \right]](../_images/math/4835d98e3dc88b84780b7e556f7751d10dc1ab74.png)

With completely precomputed  ,

,  , and the

, and the exp2() function, this

formulation minimizes the number of floating point operations while completely

preserving physics. No assumptions were made aside from the Bateman equations

themselves in this proof.

Note that it is not possible to reduce the number of operations further. This

is because  and

and  cannot be combined without adding further

operations.

cannot be combined without adding further

operations.

Implementation Specific Approximations¶

The above formulation holds generally for any decay chain. However, certain approximations are used in practice to reduce the number of chains and terms that are calculated.

- Decay chains coming from spontaneous fission are not tallied as they lead to an explosion of the total number of chains while contributing to extraordinarily rare branches.

- Decay alphas are not treated as He-4 production.

- For chains longer than length 2, any

term whose half-life is less than

of the sum of all

half-lives in the chain is dropped. This filtering prevents excessive

calculation from species which do not significantly contribute to

end atom fraction. The threshold

of the sum of all

half-lives in the chain is dropped. This filtering prevents excessive

calculation from species which do not significantly contribute to

end atom fraction. The threshold  was chosen as

because it is a reasonable naive estimate of floating point error after

many operations. If the filtering causes there to be less than

two terms in the summation, then the filtering is turned off and all

terms are computed.

was chosen as

because it is a reasonable naive estimate of floating point error after

many operations. If the filtering causes there to be less than

two terms in the summation, then the filtering is turned off and all

terms are computed. - To prevent other sources of floating point error, a nuclide is determined

to be stable when

, rather than when

, rather than when

.

. - If a chain has any

NaNdecay constants, the chain in rejected. - If a chain has any infinite

, the chain in rejected.

, the chain in rejected.

In principle, each of these statements is reasonable. However, they may preclude desired behavior by users. In such a situation, these assumptions should be revisited.

Additional Information¶

For further discussion, please see:

Note that the benchmark study shows quite high agreement between this method and ORIGEN v2.2.

References¶

| [1] | Jerzy Cetnar, General solution of Bateman equations for nuclear transmutations, Annals of Nuclear Energy, Volume 33, Issue 7, May 2006, Pages 640-645, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2006.02.004. |

| [2] | Logan J. Harr. Precise Calculation of Complex Radioactive Decay Chains. M.Sc thesis Air Force Institute of Technology. 2007. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a469273.pdf |